Footnotes on the English Translation of “A Narrative on Calligraphy” Part II

(17). 志學之年 – This refers to the age of around fifteen as noted in The Confucian Analects - Wei Zhang (《論語‧為政》):

「子曰:吾十有五而志於學。」The Master said, "At fifteen, I had my mind bent on learning.” – translated by James Legge.

(18). 味鍾張之餘烈 – In this context, 味 refers to “研究 (research)”, not “savored” as suggested by Chang and Frankel (Two Chinese Treatises on Calligraphy, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1995 :3) or “tasting” by De Laurentis (The Manual of Calligraphy by Sun Guoting of the Tang, Napoli: Universita degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale", 2011:45).

(19). 挹羲獻之前規 - 挹 refers to “揖”, which is a traditional Chinese custom to show respect of another individual by bringing together the palm of one hand and the fist of the other. Hence, in this context, it means “pay deference to”, not “absorbed” as proposed by Chang and Frankel (Chang and Frankel:3) or “drawing from” by De Laurentis (De Laurentis:45).

(20). 時逾二紀 - 紀 means “twelve years”. Hence, “二紀” means two twelve years which is twenty four years in total.

(21). 有乖入木之術 - “乖” in this context means “違背 (going against/disloyal)”. “乖” does not carry the meaning of “failed to reach” as suggested by Chang and Frankel (Chang and Frankel:3), or “lacking” by De Laurentis (De Laurentis: 45).

入木之術 – In this context, “入木(to make the ink permeate deeply into the wood)” is used to describe the ability to write extraordinary good calligraphy. There is a Chinese idiom “入木三分” wherein it described a rumor that renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi was able to produce brushstrokes so powerful that the ink could permeate into the wood by “three tenths” of a Chinese inch.

(22). 觀夫懸針垂露之異 – “異” should most likely mean “不平常,特別 (unusual, distinctive or exceptional)”, not necessarily “differences” as suggested by Chang and Frankel (Chang and Frankel:3). The last character in this sentence ,“異”, is used as an adjective for “懸針垂露” , just like “奇” is used as an adjective for “奔雷墜石” in the subsequent sentence (Line 36).

(23,24).

Source: KS Vincent Poon’s “A Model of Lanting Xu”.

(25). 鴻飛獸駭之資 –“資” means “放縱(unrestraint)” and “天性(nature)” in this context.

(26). 臨危據槁之形 – In this context, “臨” means “面對 (to face)”, “危” means “將死(about to die)”, “據” means “處於(in a state of)”, and “槁” means “死(death)”. Hence, “臨危據槁” should be interpreted as “facing near-death or in a state of death”. This sentence is used to describe that brushstrokes can be extremely frail and thin.

(27). 或重若崩雲 – In this context ,“崩” means “厚(thick)”.

(28). 纖纖乎似初月之出天崖 – “崖” means “邊際(border or edge)”. Hence, “天崖” means “the edge of the skies” which refers to the horizon.

(29). Note that in lines 35-43, Sun Guoting was describing various artistic aspects of calligraphy: the appearances of the brushstrokes (lines 35-40), the movements of the brush (line 41-42) as well as the spatial arrangements within brushstrokes of a character, or even between each character (line 43). Some of these metaphors can be found in previous literatures such as 衛鑠《筆陣圖》and 蕭衍《草書狀》.

(30). 變起伏於峯杪 – “峯” can mean “peak or tip” while “杪” can mean “微小 (small)”. Collectively, this refers to the fine tip of a brush in this context.

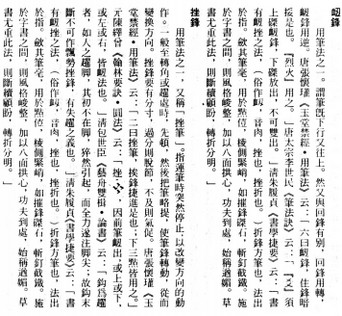

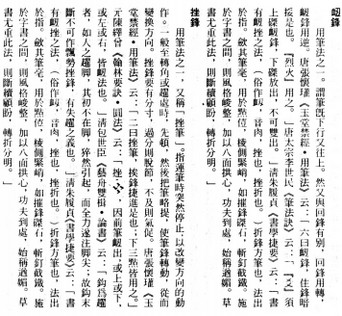

(31). 殊衄挫於毫芒 – “衄挫” refers to the specific “衄筆” and “挫筆” calligraphic techniques in utilizing the brush, as described in《中國書法大辭典》:

Source: 梁披雲,《中國書法大辭典》。廣東: 廣東人民出版社,1991, p.92。

(32). In the Book of the Later Han, Volume 47, Biographies of Ban and Liang , Ban Chao(班超) was recorded to have once said:

「大丈夫無它志略,猶當效傅介子、張騫立功異域,以取封侯,安能久事筆研閒乎?」If a man has no other ambitions and abilities, he should, at the very least, follow the examples of Fu Jiezi and Zhang Qian to establish one’s fame and titles by conquering the frontiers; as such, how can a man spend a great deal of time in occupying himself in calligraphy? (interpreted by KS Vincent Poon, Sept. 18, 2017.)Source: 范曄《後漢書》卷四十七班梁列傳。 香港:中華書局,1971,p.1571。

(33). In Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian, Volume 7, Annals of Xiang Yu, Xiang Ji (Yu) was recorded to have once said:

「書足以記名姓而已,劍一人敵,不足學,學萬人敵。」All scribes do is make lists of names, and swordsmen can only fight a single foe: that is not worth learning. I want to learn how to fight ten thousand foes. - translated by Xianyi Yang and Gladys Yang.Source: 司馬遷《史記》卷七項羽本紀。 香港: 廣智書局,出版年份缺,p.1。