Galleries and Translations > Models of Masterpieces > Models of miscellaneous Masterpieces by Wang Xizhi (part IV) 臨王羲之諸法帖 (第四部份)

Models of miscellaneous Exemplary Masterpieces by Wang Xizhi (part IV) 臨王羲之諸法帖 (第四部份)

Historical information

(I)

Wang Xizhi (王羲之) is often considered to be the most outstanding Chinese calligrapher of all time and is regarded as “The Sage of Calligraphy (書聖)” in China and Japan. Born in 303AD in an upper-class aristocratic family, Wang Xizhi started learning Chinese calligraphy at the age of seven from the renowned calligrapher Wei Shuo (衛鑠 or 衛夫人, 272-349AD). His father, Wang Kuang (王曠, ?-?AD), was a government prefecture chief (太守) and was also a calligrapher. His uncle, Wang Dao (王導, 276-339AD), was the prime minister (丞相) during the reign of Emperor Cheng of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (晉成帝, 321-342AD ). Further biographic information of Wang can be seen on my page regarding Lanting Xu (蘭亭帖).

(II)

The calligraphies presented below are my models of Wang Xizhi's handwriting found in Chunhua Imperial Archive of Calligraphy Exemplars (《淳化閣帖》). Supposedly, these handwritings were short letters and memos scribed by Wang. Although their authenticities are questionable, they are still often regarded as Exemplary Masterpieces (法帖) for calligraphers to study and observe. In the art of Chinese calligraphy, "帖(pronounced as Tie)" refers to an exemplary work that should be studied by all .

(III)

Since the originals in the Chunhua Imperial Archive of Calligraphy Exemplars (《淳化閣帖》) can be parts of or whole letters/memos scribed by Wang, translations that are provided below, if available, may not be entirely precise, for they can be interpreted out of context. Further, whether Wang had actually scribed them remains questionable. Accordingly, scholars should be wary of using these as authentic historical references.

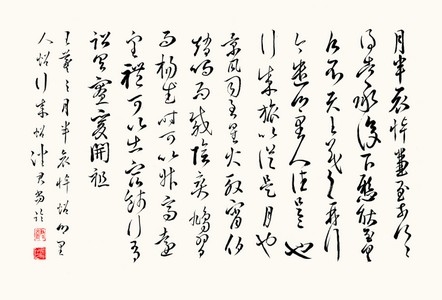

A model of Yue Ban Ai Dao Tie (月半哀悼帖), Xiang Li Ren Tie (鄉里人帖), and Xing Cheng Tie (行成帖)

35 X 52 cm

Click to Enlarge. Reserved, not available in shop.

Yue Ban Ai Dao Tie (月半哀悼帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 月半哀悼兼至,奈何奈何,得告承復下懸耿。至勿勿,願不具,王羲之再拜。

English: NA. The entire phrase may not be translated, for the context in which it was written is unknown or uncertain.

Xiang Li Ren Tie (鄉里人帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 今遣鄉里人往口具也。

English: NA. The entire phrase may not be translated, for the context in which it was written is unknown or uncertain.

Xing Cheng Tie (行成帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 行成旅以從。是月也。景風司至。星火殷宵。伯趙鳴而載陰。爽鳩習而揚武。時可以升高遠望。禮可以出宿餞行。有詔具寮。爰開祖。

English: NA. The entire phrase may not be translated, for the context in which it was written is unknown or uncertain.

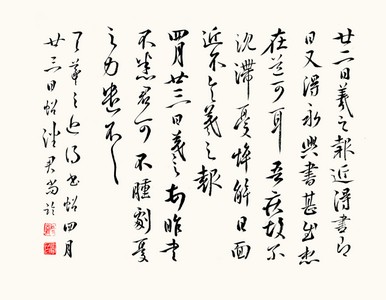

A model of Jin De Shu Tie (近得書帖) and Si Yue Er Shi San Ri Tie (四月二十三日帖)

35 X 52 cm

Click to Enlarge. Reserved, not available in shop.

Jin De Shu Tie (近得書帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 廿二日羲之報,近得書,即日又得永興書,甚慰,想在道可耳。吾疾故爾,沈滯,憂悴解日。面近不具。羲之報。

English: NA. The entire phrase may not be translated, for the context in which it was written is unknown or uncertain.

Si Yue Er Shi San Ri Tie (四月二十三日帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 四月二十三日羲之頓首,昨書不悉,君可不,腫劇憂之,力遣不具。

English: NA. The entire phrase may not be translated, for the context in which it was written is unknown or uncertain.

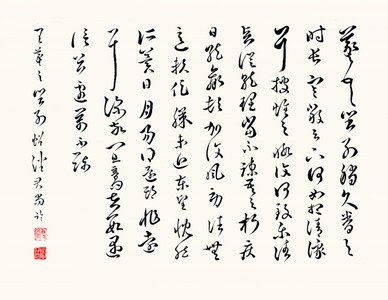

A model of Kuo Bi Tie (闊別帖)

35 X 45 cm

Click to Enlarge. Reserved, not available in shop.

Kuo Bi Tie (闊別帖):

Original Classical Chinese: 羲之頓首。闊別稍久,眷與時長,寒嚴。足下何如?想清豫耳。披懷之暇復何致樂。諸賢從就,理當不疏。吾之朽疾,日就羸頓;加復風勞,諸無意賴。促膝未近,東望慨然。所冀日月易得,還期非遠耳。深敬!宜音問在數。遇信忿遽,萬不一陳。

English: [Wang] Xizhi knocks his head on the ground**: We have been separated for very long. Affection grows with time. How are you in this bitter cold? I only wish you peace and happiness. The leisure to open our hearts to each other—when will we have this supreme joy again? … My illnesses of decay are making me more frail and tired every day. On top of this I again contracted Wind due to exhaustion. All this is utterly bad. We won’t be sitting knee to knee anytime soon. I am looking east with deep emotion. I only hope that the days and months will pass easily and that the time of your return may not be far away. With deep respect, if it should suit you to send me a message, do so as often as possible. In a hurry to still catch the messenger I can only set out a tiny fraction [of what I wanted to say]. (Translated by Antje Richter & Charles Chace in The Trouble with Wang Xizhi: Illness and Healing in a Fourth-Century Chinese Correspondence (T’oung Pao 103-1-3 (2017) 33-93))

**"Wang Xizhi knocks his head on the ground (羲之頓首)" should be better interpreted as "Wang Xizhi gratefully bows in respect and deference" (KS Vincent Poon).